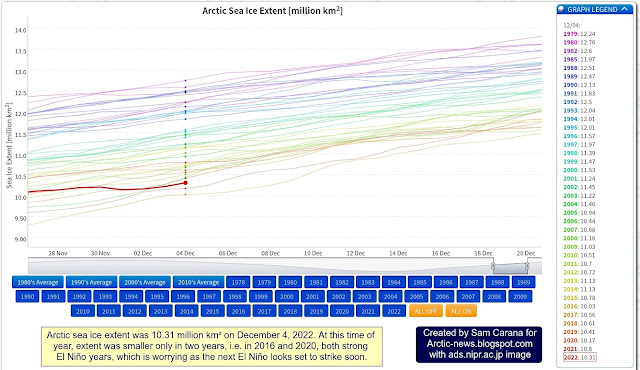

Arctic sea ice extent was 10.31 million km² on December 4, 2022. At this time of year, extent was smaller only in two years, i.e. in 2016 and 2020, both strong El Niño years. With the next El Niño, Arctic sea ice extent looks set to reach record lows.

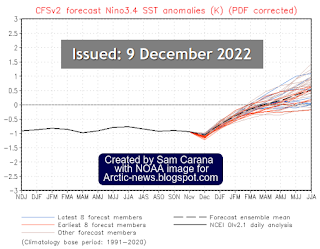

The NOAA image on the right indicates that, while we're still in the depths of a persistent La Niña, the next El Niño looks set to strike soon.

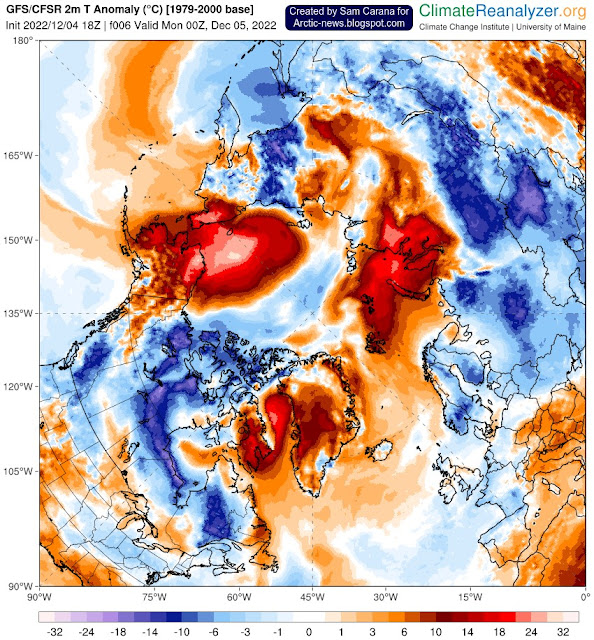

The image below shows a forecast for December 5, 2022, of 2m temperature anomalies versus 1979-2000, with anomalies over parts of the Arctic Ocean near the top end of the scale.

On December 6, 2022, the Arctic was 6.63°C or 11.93°F warmer compared to 1979-2000, as illustrated by the image below.

The image below shows the daily average Arctic air temperature (2m) from 1979 up to December 6, 2022.

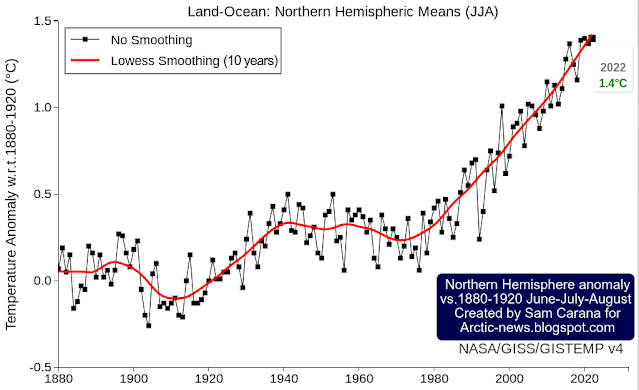

Given that we're still in the depth of a persistent La Niña, these currently very high air temperature anomalies indicate that ocean temperatures are very high and that ocean heat is heating up the air over the Arctic.

Additionally, ocean heat is melting the sea ice from below.

Accordingly, Arctic sea ice has barely increased in thickness over the past 30 days, as illustrated by the navy.mil animation on the right.

This leaves only a very short time for Arctic sea ice to grow back in thickness before the melting season starts again, which means that there will be little or no latent heat buffer to consume heat when the melting season starts.

Furthermore, rising temperatures and changes to the Jet Stream contribute to formation of a freshwater lid at the sea surface at higher latitudes, resulting in further heating up of the Arctic Ocean.

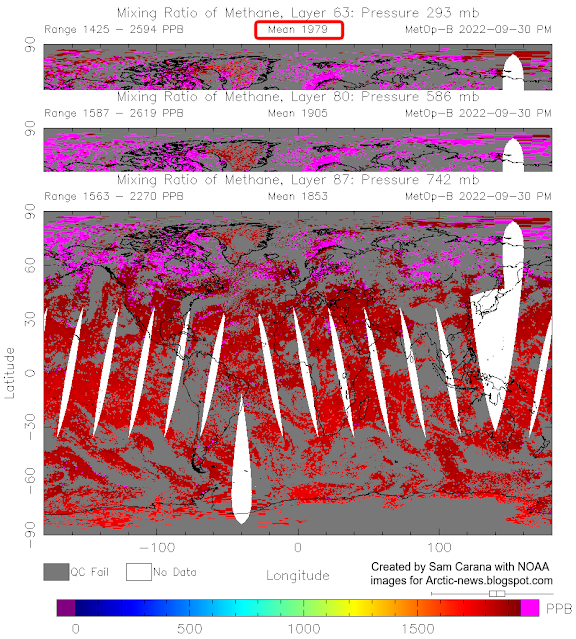

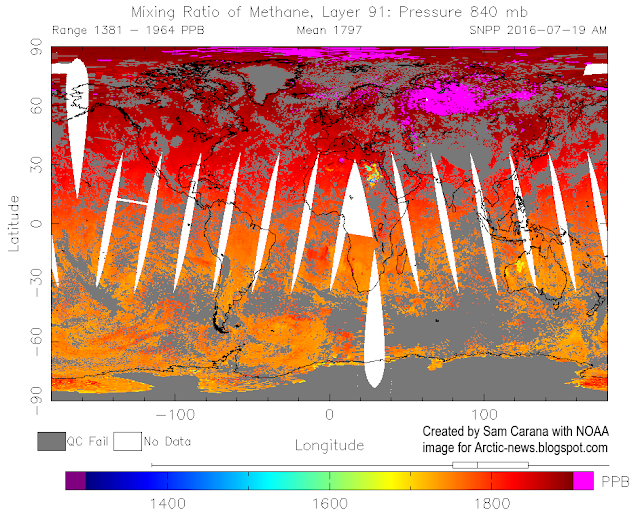

As a result, more heat threatens to penetrate sediments at the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean that contain vast amounts of methane in hydrates and free gas, and result in abrupt release of huge amounts of methane, dramatically pushing up temperatures globally.

The situation is dire and the right thing to do now is to help avoid or delay the worst from happening, through action as described in the Climate Plan.

Links

• Vishop sea ice extent

https://ads.nipr.ac.jp/vishop/#/extent

• NOAA ENSO: Recent Evolution, Current Status and Predictions

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf

• nullschool.net

https://earth.nullschool.net

• Climate Reanalyzer

https://climatereanalyzer.org

Accordingly, Arctic sea ice has barely increased in thickness over the past 30 days, as illustrated by the navy.mil animation on the right.

This leaves only a very short time for Arctic sea ice to grow back in thickness before the melting season starts again, which means that there will be little or no latent heat buffer to consume heat when the melting season starts.

Furthermore, rising temperatures and changes to the Jet Stream contribute to formation of a freshwater lid at the sea surface at higher latitudes, resulting in further heating up of the Arctic Ocean.

As a result, more heat threatens to penetrate sediments at the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean that contain vast amounts of methane in hydrates and free gas, and result in abrupt release of huge amounts of methane, dramatically pushing up temperatures globally.

|

| [ The Buffer has gone, feedback #14 on the Feedbacks page ] |

Links

• Vishop sea ice extent

https://ads.nipr.ac.jp/vishop/#/extent

• NOAA ENSO: Recent Evolution, Current Status and Predictions

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf

• nullschool.net

https://earth.nullschool.net

• Climate Reanalyzer

https://climatereanalyzer.org

• Naval Research Laboratory - HYCOM Consortium for Data-Assimilative Ocean Modeling

https://www7320.nrlssc.navy.mil/GLBhycomcice1-12/arctic.html

• Albedo, latent heat, insolation and more